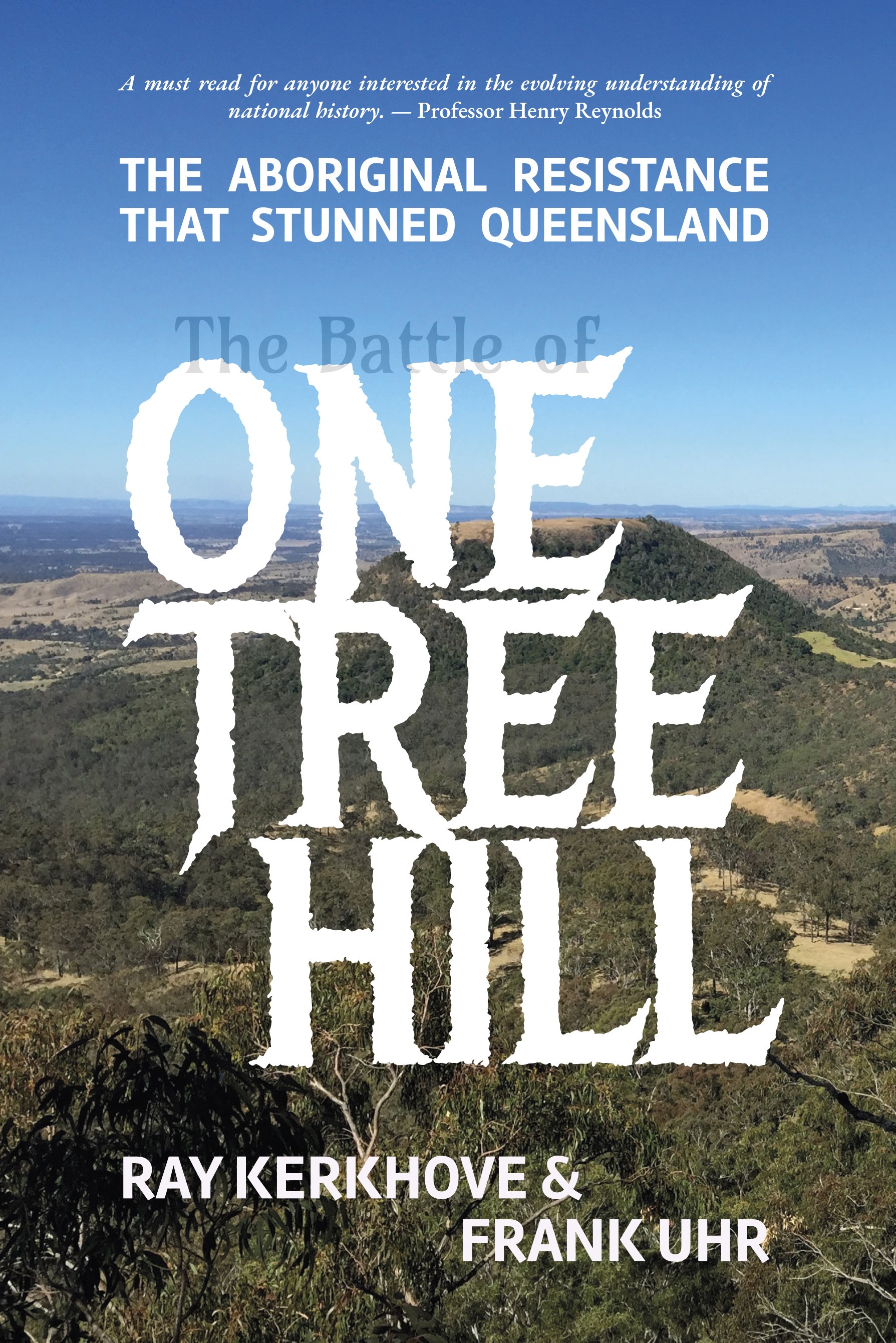

The Battle of One Tree Hill: The Aboriginal Resistance that Stunned Queensland

Accounts of frontier violence have grown since Bill Stanner’s criticism in the 1968 Boyer lectures of Australian history’s wilful ignorance of Aboriginal people and Aboriginal history. Ground-breaking works by Henry Reynolds and Lyndall Ryan have revealed the violence and the complicity of colonial authority, and more recent texts by historians such as Stephen Gapps have shown the resistance of Aboriginal people to invasion. The Battle of One Tree Hill by historians Ray Kerkhove and Frank Uhr sits firmly alongside these histories. It tells of the success of a range of Aboriginal groups in the Darling Downs and Lockyer region, working together to defeat colonists in the Battle of One Tree Hill.

READ REVIEW

↓

The Battle of One Tree Hill: The Aboriginal Resistance that Stunned Queensland

Ray Kerkhove and Frank Uhr | 2019

Showing the leadership of Old Moppy and then his son, Multuggerah, Kerkhove and Uhr demonstrate the strategic alliance and planning of the ‘Mountain Tribes Alliance’ during a period of resistance in the 1840s that culminated in victory at the battle of One Tree Hill (Mount Table Top). These are the names used by the authors, who had to face the challenge colonisation presents in this field of study, namely some loss of memory of ancestors’ names and therefore a reliance on colonial nomenclature. They state: ‘to avoid asserting borders or unity that may or may not equate with the “on ground” situation in south-east Queensland at the time of contact (or today), or which may belittle the complexity of traditional interactions…we will utilise the descriptions given by settlers in early accounts’ (p. 28).

The book traces the alliance’s efforts to negotiate with the invaders, to practise Aboriginal law and to prevent white people from settling in the region. It tells of a vast body count: evidence of, and hints at, mass killings of Aboriginal people, some of whom are identified in the book, although puzzlingly the appendices only list colonists who were killed during this time. The lawless behaviour of the invading colonists and the complicity of colonial office holders, along with the incapacity of Anglo law to protect all the subjects it claimed to shield, is also revealed.

Kerkhove and Uhr rightly position Old Moppy and Multuggerah as the heroes of this story. They outline Old Moppy’s efforts to build an alliance of local Aboriginal groups through a toor (conference) during the bunya season, before describing Multuggerah’s leadership after Old Moppy’s murder, including at the battle of One Tree Hill. In this battle Aboriginal warriors blocked in and attacked a convoy of wagons bringing much needed food and shearing supplies for colonists. Using a narrow ravine and logs, Aboriginal men sent rocks from their vantage point above as the colonial invaders attempted to climb up to fight them, then headed to the safety of the Rosewood Scrub, which provided food and water, as well as holding spiritual importance. The authors argue that, whilst there had been years of attacks – sometimes by small groups and sometimes involving a hundred or so warriors – the Battle of One Tree Hill demonstrated the greatest planning and alliance building, which resulted in the defeat of the colonial invaders. The section focussing on that battle is the strongest of the book.

This tribute to the alliance is underpinned by a great deal of research, drawing on archives, oral histories and traditions of local Aboriginal people. The bibliography is impressive. There were, however, times when I found the book’s narrative a little difficult to follow. I was not sure if my confusion was because of my unfamiliarity with Queensland’s history or due to the style of short sections with subheadings that distracted from the flow. The authors do provide brief biographies for many of the writers of the primary sources they use, yet the reader is left to do work to try to understand the ‘agenda’ (p. 1) of each colonial author. I feel there was a missed opportunity not to include more context gleaned from the authors’ years of research (including in secondary sources) and the knowledge gained from their engagement with local Aboriginal families. Despite these concerns, this book deserves a wide audience.

I appreciated the discussions of Aboriginal law and practices throughout the text – for example the description of the permanent camp (p. 82). The use of Aboriginal sources, including artwork, places and archaeological sources added to the story and showed in practice the worth of such texts, as discussed by Amangu Yamaji academic Crystal McKinnon (From Scar Trees to a ‘Bouquet of Words’: Aboriginal Text is Everywhere). Laying out information where there was no clear agreement, such as when Multuggerah died (pp. 205-207), was a good decision, because it reinforces the silences in the record mentioned in the introduction and the disruptive nature of colonial invasion to this part of the world.

It is with a generosity that the authors invite people not only to read but to continue the history work they have started. A quote from Henry Reynolds graces both front and back covers; his endorsement is well deserved. As treaties and truth-telling processes are considered across the many Countries of this land, histories such as this have great importance. They discredit ideas of colonisation as an ordered, lawful process, and reveal the capacity of Aboriginal people to strategise to defend their Country and act within their law.

Reviewer: Dr Amanda Lourie, PHA (Vic & Tas)

The Battle of One Tree Hill: The Aboriginal Resistance that Stunned Queensland is published by Boolarong Press.